The Many Faces of Nathan Fielder

or, When the Mask Slips

I’ve recently been making my way through the show Nathan for You. It’s been a trip.

Normally, I’m quite averse to any sort of comedy that involves the public. I’m extremely susceptible to second-hand embarrassment (and cringe. They might be the same thing); I straight up dislike stand-up comedy for this reason, largely because the genre has devolved into TikTok clip crowd work. Gross.

Nathan for You has been my cringe exposure therapy, which is truly the definition of diving headfirst, because Nathan Fielder is a sociopath. I mean so genuinely: I think it takes utter indignity to manipulate people in the way that he does. I’m sure I’m not alone in noting this. Yes, there are moments where the show tries to humanize him, but in my opinion we can only say they serve to humanize the character Nathan, not the agent that is constructing him. More on that later.

For those uninitiated, Nathan for You follows Nathan Fielder, a dead-pan facsimile of the Canadian comedian, as he “helps” small businesses. The comedy of the show stems from Nathan suggesting utterly outlandish ideas to business owners with a straight face, and then enacting them in all of their absurdity. It ran for four seasons on Comedy Central before he moved on to other projects, notably The Rehearsal with HBO.

All said, I love the show. I think it’s a fascinating exploration of desperation, alienation, and absurdity, even if it sometimes abuses those things for entertainment. And, crucially, it’s really funny.

I wouldn’t call Nathan for You explicitly mean-spirited, but when I’m watching it, I can’t shake the feeling that the eclectic mix of people Nathan chooses to feature are intentionally targeted for certain traits that make them either gullible, naive, or desperate enough to say yes to anything—especially for a quick buck. There’s a reason he often relies on Craigslist to find participants.

There is a distinct sense of othering in some episodes, as if Nathan, while inserting himself into people’s lives and humiliating scenarios, is doing so with palpable irony. There are certain scenes where I can feel him winking at me, letting me know he’s laughing alongside me, that he isn’t the fool but the master, his grinning spectre looming over my shoulder like a friend showing me a youtube video, waiting for me to guffaw at their favourite parts, haunting my dreams with his malign form hunched in a dark editing room, face gnarled into a ghoulish grin and illuminated by the cold light of a monitor, him the predator, us the pr—

*Ahem*. Sorry for the hyperbole. I'll reign it in.

The presence of a puppeteer is diffuse in Nathan for You, and the more I watch, the more I find myself trusting in his abilities, believing that he is a shepherd of audacious comedy, always one step ahead—an authority on performance art.

However, there was one episode where this veneer faltered, and in doing so, it revealed a whole new dimension to the show.

SMOKERS ALLOWED

The episode I’m referring to is season three, episode five, titled “Smokers Allowed”. The aim of this episode is to restore the smoking privileges of a dive bar by designating the space a theatrical performance. To this end, Nathan stages a “play” for a couple of bystanders to bypass smoking regulations.

The joke is that the play Nathan stages is simply a regular evening at the establishment. The curtains open; the two audience members observe patrons going about their usual bar business (people drink, chat, and—crucial to the premise—smoke); the curtains close.

After the play, the two spectators are interviewed, wherein they speak favourably of it. Feeling validated as an artist, Nathan decides to hire a troupe of actors to professionally recreate the play, and performs it for a crowd of a few dozen people, who receive it mostly poorly.

Now, my qualm with this episode stems from the premise.

As if to accuse the initial two audience members of being dumb or disingenuous, Nathan orchestrates dozens of people, likely for many hours of work, to rub in their faces that the initial play in fact sucks, and that Nathan knows good theatre, can distinguish between art that has merit, and art that’s bust.

The other explanation is that Nathan is trying to poke fun at how obsequious people become with a camera on them. However, this theory is troubled by the audience at end of the episode, who are not shy about being critical towards the recreated play. My intuition tells me there is something more malicious at play.

To my point, here’s the scene where Nathan shows a clip of the play to the chair of the Glendale community college theatre department, to determine if it shows any promise.

She engages with the play earnestly, absorbs the scene not to rip it apart, but to find meaning in it. She identifies which characters she finds interesting, speculates about potential narratives, and describes it as “slice of life” theatre. She even offers some comparisons to the works of other playwrights.

As Grace Benfell says in this excellent interview, good criticism involves a dialogue between the critic and the art.

“I think that criticism is dialogue. And even if your only citation is the [art] itself, you’re still talking to a thing that’s separate from you and that feels important to me. That’s the heart of the thing, that you are having a discussion with something. That means taking it seriously in a real way.”

That, I think, is what Jeanette is doing in this scene. She meets the play not where it might be perceived, but where it is at. These are all things you would expect someone versed in their field to be able to do with humility.

And the show mocks her for it.

This scene, to me, is emblematic of Nathan’s snicker, a malicious prank played by a school-yard bully. It denigrates her—admittedly charitable—critique, and, by extension, the value of her expertise. It does not take her, or the medium, seriously.

The derision of the arts has been in vogue for some time now. The humanities are often juxtaposed with STEM/economic fields, and labelled useless and invaluable in comparison. Women and gender studies, for example, have been the butt of the same joke for decades, espoused by people who do not understand what the discipline even pertains to, and who believe it is a waste of time to find out. Or, worse, they think they have it figured out already, and that there is nothing left to learn.

Universities have, in many instances, fully gutted humanities departments in lieu of making cuts to STEM or business fields. Not to mention, people genuinely think AI is the future of art (?????).

This general apathy towards the humanities belies a fundamental lack of curiosity, and that lack appears to be the crux of this episode.

This struck me as quite philistine, and frankly disappointing. Is it really so outlandish to find this play meaningful?

SPLIT-FICTION

While Nathan for You is ostensibly an unscripted show (at least insofar as the people involved in the stunts don’t seem aware they’re stunts), there is a fair degree of theatre involved, specifically with the eponymous character. Doubly so in this episode.

If there is a through line in N4Y, that is, something that persists or is thematically present in each episode, it is the division of the subject of Nathan. This division is both explicit and implicit, and it is threefold: Within the character Nathan, there is the insecure, lonely interior who projects the confident, successful exterior—the ideal he is pretending, unconvincingly, to be. Throughout the show, the latter is what the character Nathan tries to convince the viewer he is, but through a plethora of awkward instances, as well as a handful of intimate moments, the former breaks through, revealing the connection and validation starved self. These two can be classified as the explicit divisions, because they are expressly part of the narrative of the show. Here’s an iconic clip from “Smokers Allowed” to demonstrate this partition:

Yet, because Nathan Fielder decided to name this character after himself, there is another, implicit division: the actual Nathan, the one orchestrating the show and constructing this character—the authentic Self.

While the identities of the character Nathan are the fulcrum of the show, the premise of this episode seems to reveal an implicit bias of his creator. The mask slips, so to speak.

IDENTITY

The invocation of psychological elements in the narrative of N4Y makes it ripe for armchair analysis, particular through the lens of identity.

Identities are fluid; that’s what makes people interesting. If you could talk to someone once and know their true self, then there would be nothing to discover. The caveat of this depth, however, is that we can never fully know others. This is the essence of drama: we can speculate, use every analytical tool at our disposal, yet there will always remain untenable elements of the soul. All we can do is form categories, and fit people as closely into their grooves as we can. This form of typology can prove fruitful, but must always be accompanied by an acknowledgement of its incompleteness. The pursuit can bear revelations, but never unadulterated understanding.

This interminable depth extends to ourselves, too. This truth, I believe, is relatively easy to prove: When you hang out with certain people or enter certain spaces, your demeanor, humor, and speech often changes; when you’re at work, you became the archetype that is expected by the job; even when you're by yourself, there are times where you can catch yourself projecting and deflecting your thoughts, particularly when they broach unsavoury aspects of your personality, or your regrets.

It is nigh impossible to nail the self down; it’s too diffuse. We all wear a multitude of masks on any given day. As Rush (paraphrasing Shakespeare) sang: all the world's a stage, and we are merely players. There is theatre in the mundane, because the mundane is theatre. I believe this is why “people watching" is such a common activity.

There are many thinkers we can look to for backup here. Sartre explored authenticity by studying waiters; Freud has much to say about archetypes; Jung’s concept of “the persona” is apt. Instead, I’d like to invoke a book on Lacan that I read recently, if only so I can show off its cool illustrations.

THE IMAGE

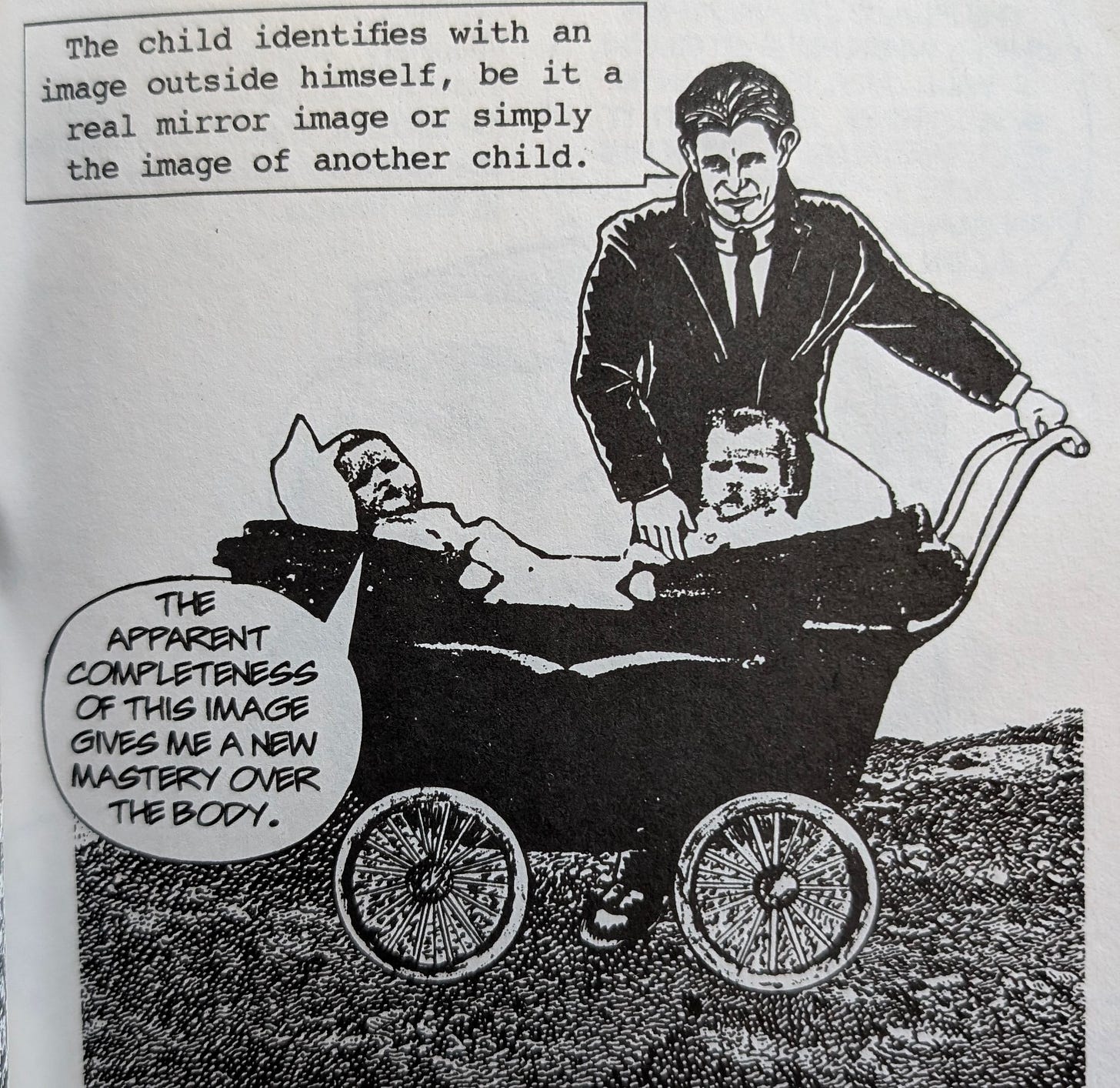

In short, Lacan believed that we first identify with an image, and that we “master their relation to [our] body” through mimicry:

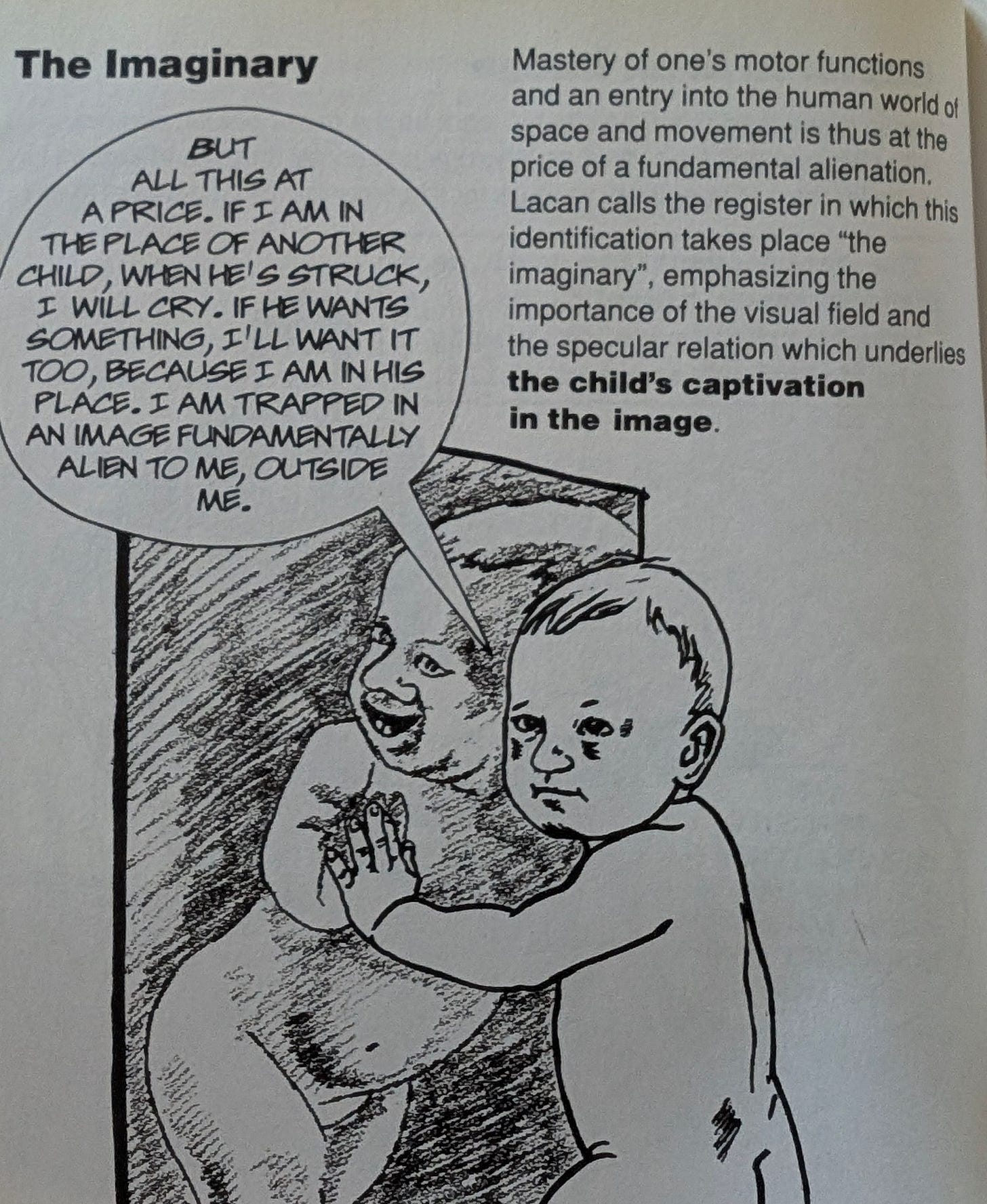

He theorized that what we refer to as our “Self” is actually just a projection, or a reflection.

For example, when one is born, their mother holds them up to a mirror, and says, “that’s you”. You are told/shown what you are. Therefore, your conception of your Self always comes from outside. This is what the book refers to as being “captured in [your] environment.” Subjecthood exists in the realm of apperception: in order to know yourself, you must turn yourself into an object, a concept that can be analyzed. Your identity, then, is in constant relation with things. It is conditioned/enforced by the imaginary, but also by our symbolic networks. For example, I learn that I am stubborn because my partner accuses me of being so.

Further, because identity is given out there, it is in some ways scientific. By this, I mean that our identity is constantly subject to feedback. The self is constructed, and experimental; our variables are always being influenced and tuned. We mirror others, reflect, see what sticks, and what doesn’t. Sometimes we’re not even aware of the changes until someone points them out. To be human is to be invariably in flux.

However, relying on something outside of one’s self for completeness inevitably leaves a cardinal lack within, a brute disconnection, or alienation. This is the intangible seat of pure subjectivity. Ironically, the apparent completeness of another is the cause of our own incompleteness.

The lack of an absolute completeness, if I’m permitted to postulate, is something we are constantly at odds to fill; it can be the source of insecurity, or, according to Zizek, the source of our freedom.

With the explicit division of the self in the character Nathan, the show (and by extension its creator) also seems to acknowledge that the Self is a performance. Further, the character Nathan’s essential lack can be understood as his desire to be perceived as smart, cool, and well-liked. This is what Lacan would call his “ideal ego”, a projection that, by falling short of it, reveals his awkward, vulnerable self.

I think the actual Nathan, to some degree, shares the same ideal ego as the character he created. He wants to be perceived as a great talent, but the insecure, implicit face we glimpse in “Smokers Allowed” shows that he is just as vulnerable and insecure as his character.

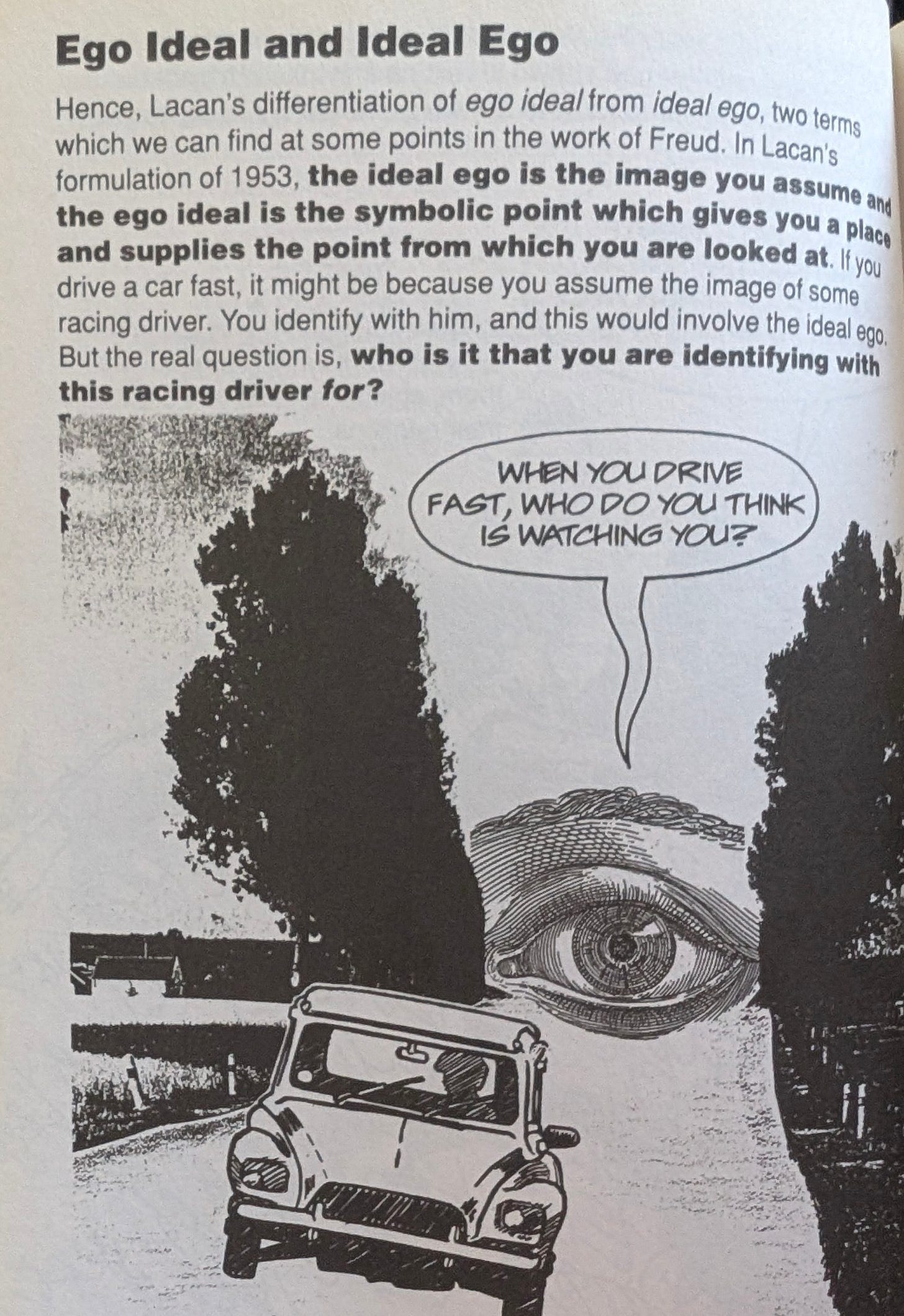

This face exists beneath the plane of images and projections. It dwells in the symbolic, the “ego ideal”:

It represents Nathan’s insecurities surrounding his perception, and his art. He derides theatre and performance art in this episode for the approval of a presupposed audience, while at the same time demonstrating both his aptitude for it, and its ubiquity.

To conclude, while it is entirely valid to find the bar play boring or meaningless (that is still engaging earnestly with it), to ridicule those who do see its worth betrays a certain ignorance and/or arrogance. I do not know if this slip of the mask is intentional. Perhaps this is just another aspect of Nathan’s masterminding? Or, maybe my interpretation is completely off the mark, and this episode is just a case of taking a bit and seeing how far it can go? I can only speculate.

What I can say with certainty is that the show is better off with this complexity, and that its vulnerability, both explicit and apparent, has deepened my appreciation for it.

Needless to say, I’m looking forward to watching The Rehearsal!

References

“Smokers Allowed”. Nathan for You

Darian Leader and Judy Groves’ “Introducing Lacan”